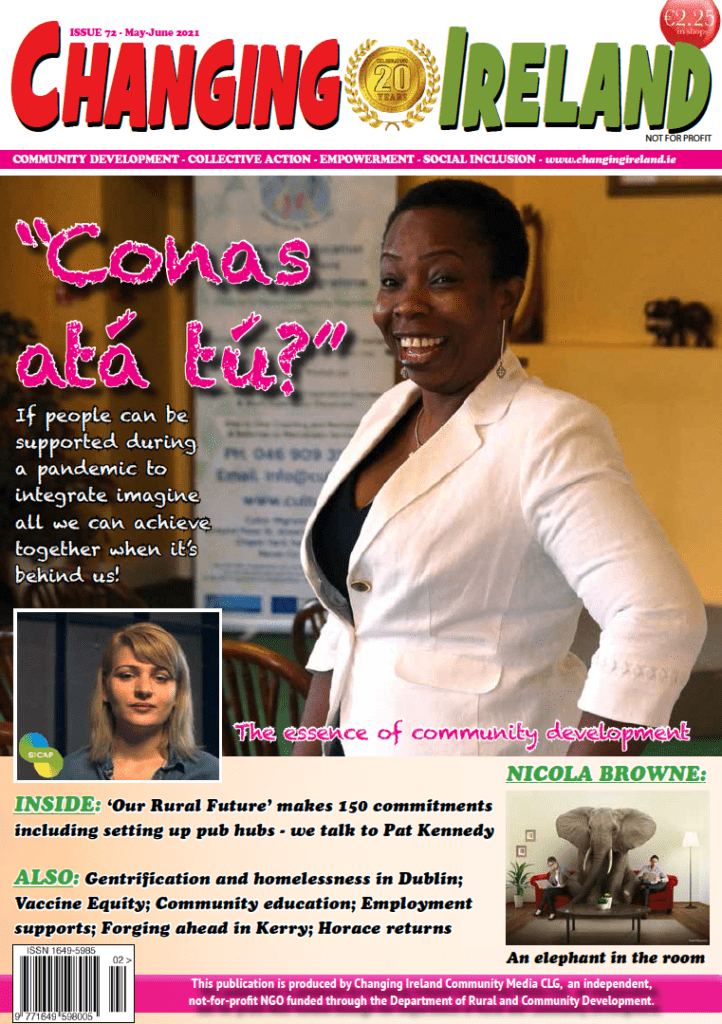

The pandemic has shown us more than ever the importance of self-care, writes Nicola Browne. She asks – why are social justice organisations so slow to practice what they preach when it comes to wellbeing?

BY NICOLA BROWNE

Where I live in Whiteabbey, on the outskirts of Belfast, many of my neighbours are older women who live alone. Every other day at 4pm during the first lockdown, one lady across the street opened her front door and set up a chair just inside. A few minutes later, doors opened and other women in the street carried out their kitchen chairs and sat metres from her front door, chatting and laughing, before disbanding after an hour or so and going in for dinner.

Like others, I’ve drawn comfort during the pandemic from the natural environment, watching the wild garlic emerging and new buds on the trees at nearby Hazelbank Park. But the rhythm of my neighbours’ outdoor meetings has been a daily reminder of the importance of connection and care, not as a one off purchased treat, but as a practice built into the everyday.

Discussion around self-care has boomed during the pandemic. As activists we have felt both the urgency of opportunities for change that crises bring, alongside feelings of exhaustion, powerlessness and inadequacy at the scale of the task ahead.

But as the months have passed, the evidence of burn-out and fatigue is becoming clear.

Many of us are drawn to activism as an expression of our values around equality, justice and dignity. At its best, working for change can be a source of joy and community and yet it can also feel dispiriting and disillusioning when we are bereft of successes. And yet, as author Bonnie Honig* points out, “Exhaustion is a feeling that autocrats like us to have.” Neglecting care of ourselves and our community plays to the interests of those who wish to uphold the status quo.

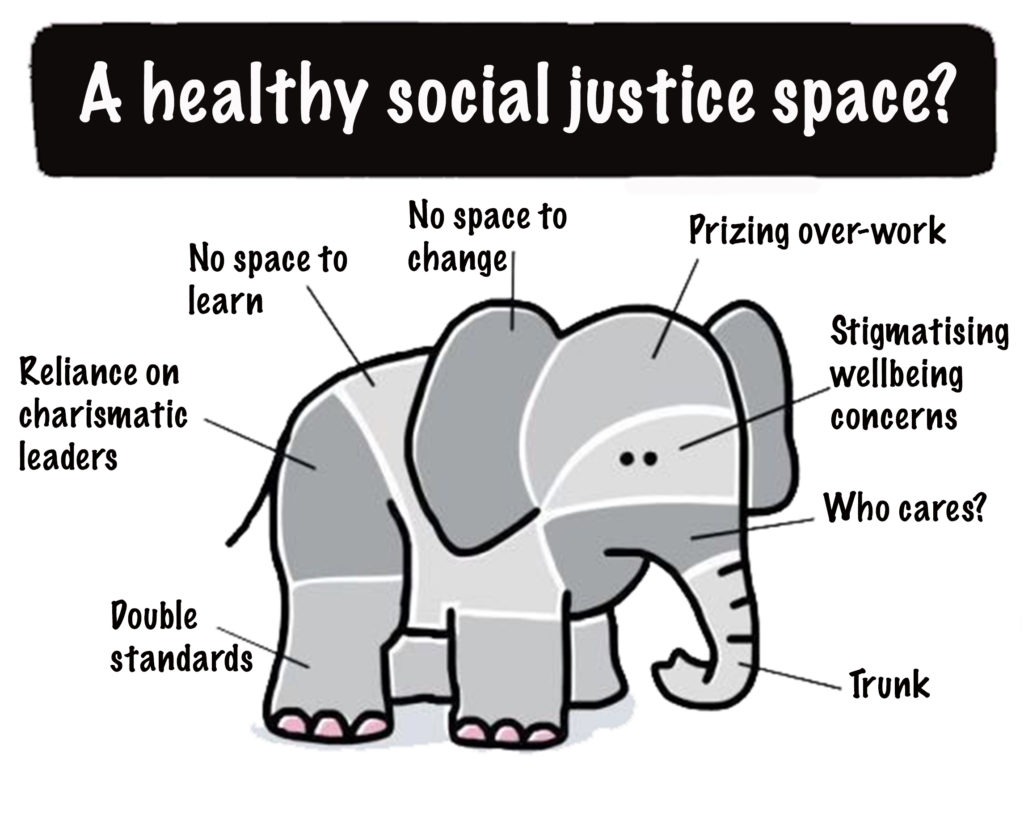

We all need to grapple with the fact that many human rights and social justice organisations do not respond well to the challenges of maintaining the wellbeing of their staff, and can be steeped in the standards based in the very white dominant and capitalist values that we oppose in our campaigning work.

• Elephant found wandering anonymously around Instagram. Graphic additions by Changing Ireland.

Human rights organisations in particular are increasingly recognising these systems as the source of many of the injustices we fight. And yet it can be difficult to avoid absorbing these values into our own core. We may judge ourselves based on our productivity, put urgency around our external deliverables and not our internal reflection practices.

We may see our own work as much more important than that of others around us. In her article ‘Is your social change organisation a pressure cooker?’ US racial justice activist Deepa Iyer** identifies productivity, purity and personality (among others) as characteristics of social justice spaces which can result in:

– prizing over-work,

– having no space to learn or change, and,

– reliance on charismatic leaders.

As sociologist Emma Craddock points out, direct action is often thought of as ‘true activism’ and privileged over the many other roles which make up a campaign – admin work, logistics and care.

Inspiration can always be drawn from the networks of care we see around us if we recognise their value. We should not see them as inconsequential because they are feminine, local and unpaid. Putting the ‘human’ in human rights requires us to consider how our activist practices must change.

To act with integrity in our work means it is not acceptable for our workplaces to preach one standard of dignity and care to government and public bodies, and deliver another to our colleagues. Instead we must bring the human rights values of dignity and equality to life in our work and activist spaces and look at how we care for each other through the same human rights lens we use for the rest of our work.

1. Name the issues

This requires naming and clearly acknowledging the common habits that arise among activists that get in our way. Margaret Satterthwaite and others carried out extensive research into human rights culture which “too often valorize(s) martyr and saviour mentalities, and stigmatise wellbeing concerns”. As a close friend and activist pointed out to me recently, “To say that care is unnecessary for social justice work is to speak from a position of privilege.”

2. Look at our organisations

Adequate rates of pay, good terms and conditions, anti-racist, ableist, sexist hiring practices and collective bargaining are the fundamentals.

But we must go beyond one-off trainings and move towards structural changes in the way our work is done.

– We can examine our cultures and the values our leadership is demonstrating.

– We can change the messages we send about what we value in appraisal systems and in decision-making processes.

– We can be explicit about embracing the rhythms in our work – building in time for practices like action learning and reflection.

3. Imagine something better

One inspiring example is the ‘Happiness Manifestx’ (52 colourful pages of commitments) released in 2019 by a Canadian not-for-profit called the Frida Fund, a foundation for young feminists. The word ‘Manifestx’ points to the political nature of their commitment to self-care. Identified through a series of reflective conversations, it includes commitments on the part of workers to communicate when they are overtired, renounce guilt, and delete their work email from their phone.

As an organisation, the Frida Fund committed to clear decision-making and communication processes, to provide training and coaching, and to a four-day week, with Fridays spent reading and writing about feminist organising.

The pandemic has shaped us all, and has impacted both the issues we work on and the way in which we do that work. If we are to truly put the human back into human rights, we must place our values at the heart of our everyday work, and protect our new and established activists, in order to preserve their vital knowledge of struggle for the future.

FURTHER READING

• Nicola Browne has written in detail on the topics touched on in this article. Download her guide – launched in April – from: https://www.changefromthegroundup.org/disruptive-rights

* Self-care tips from Bonnie Honig: https://bit.ly/3strlMa

** Read Deepa Iyer’s article ‘Is your social change organisation a pressure cooker?’ – here:

http://bit.ly/Isitacooker

Download Frida’s Happiness Manifestx as a PDF via Google.

On Twitter

Deepa Iyer:

@dviyer

Emma Craddock:

@EmmaCraddock89

DOWNLOAD & READ THE FULL MAGAZINE (PDF): Spring 2021 Edition